Comic Art Friday exclusive: Inkwell Awards founder Bob Almond (part one of two)

You've arrived at a good time, friend reader. Your Uncle Swan has a special treat in store for today's Comic Art Friday... and for next week's, as well.

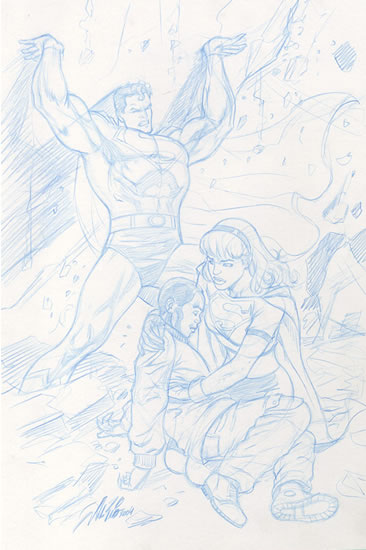

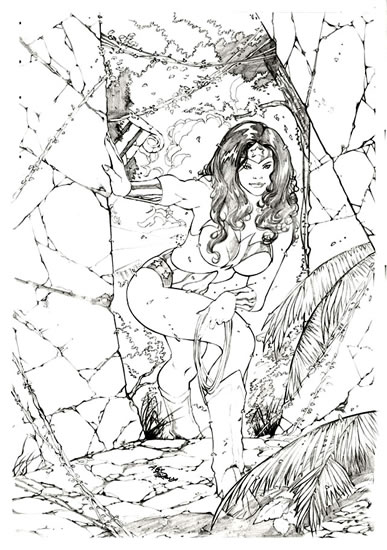

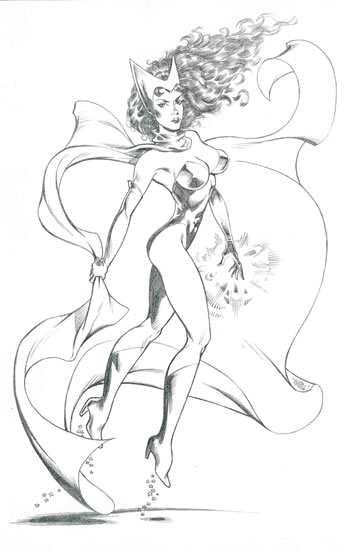

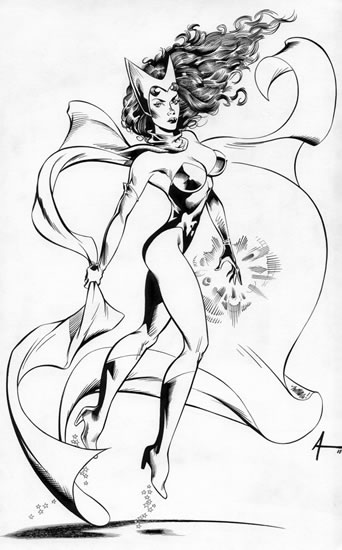

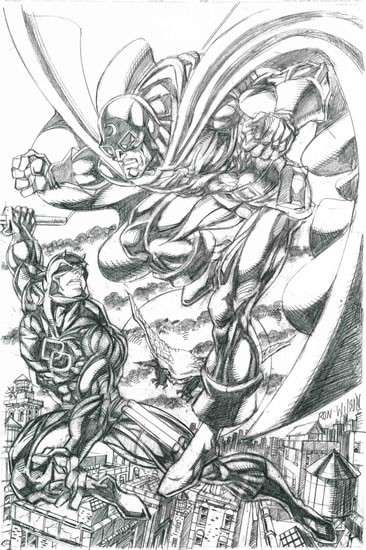

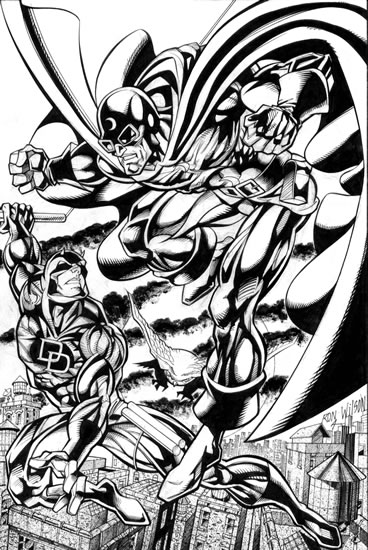

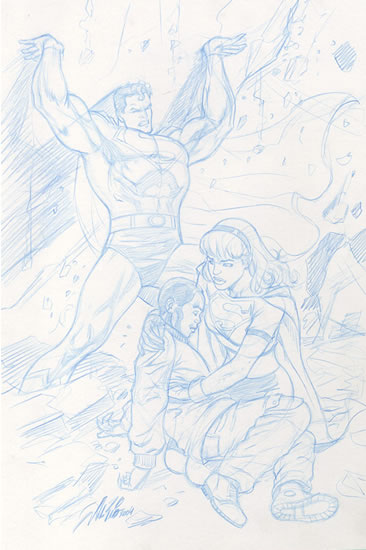

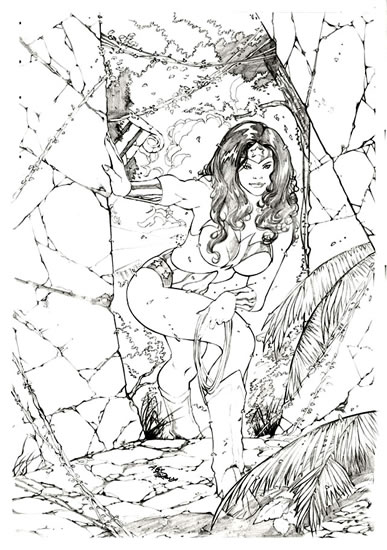

If you drop by this august establishment frequently, you'll recognize the name of comic book artist Bob Almond, whose titanic talent has graced many a Comic Art Friday. One of the most gifted inking specialists in the industry, Bob is a master at transforming pencil drawings into beautifully finished art.

Over the past few years, Bob has accepted about 30 commissions from me. It's fair to say that my art galleries would be drastically different were it not for the brush strokes and pen lines of the man other collectors and I affectionately call "The King of Ink."

Recently, Bob teamed with a stellar assemblage of comic industry insiders to create the Inkwell Awards, a soon-to-be-annual celebration of inking artists and their craft. Through his "Inkblots" column in Sketch Magazine, Bob developed the concept of acknowledging the often overlooked (and in my opinion, tragically undervalued) artists who, as Bob defines it, specialize in:

SSTOL: Bob, what inspired you to create the Inkwell Awards? And why do you think that inkers don't get more recognition in the comics community?

Bob Almond: Actually, to combine these related questions into one answer, the fact that ink artists don't [get their just recognition] is what inspired me to create the awards. One reason for the latter is the fact that "inker" is almost exclusively a comic book industry product. As such, the name doesn't have a precedent for people comprehending what exactly s/he does.

In general, everyone knows what a penciler does, and they can easily determine that they draw. Same with the letterer, colorist, and even the editor. Not the inker. The common understanding from the public is that we fill in the blacks, or that we color, and, of course, that we "trace," which is the simplest and most ignorant of definition of our craft. If that was all we did, then anyone off the street could do it.

The other reason is that, for whatever reason, the status of inkers [within the comics industry] has been diminished of late. Their credits have been absent from some solicitations, reprint collection covers, and reprint sample art. Some major conventions haven't listed inkers in their guest lists, and some industry awards don't give them their own category. Inkers used to be one of the top three creator categories, but they've lost some leverage in that arena due to — in our opinion — less recognition for their work and lack of information.

We inkers certainly don't follow this line of work for the money. We do it for the love of the medium and craft, and for the credit. This is what motivated me to initiate an effort to give back to the invisible inker — often unsung, like the bassist of a band, who's not a rock star like the lead singer or guitarist.

We want to show appreciation to the ink artists, as well as have our site consisting of information and resources to help educate and inform the fans on what we do. Not to elevate our work to that of brain surgery or anything pretentious — we just feel it is an essential part of sequential art production in the area of quality control and storytelling enhancement.

SSTOL: In this age of computer graphics, is inking a dying art?

Bob Almond: Dying, no. Diminished, yes. But not necessarily due to computer tech. The comic book implosion of the '90s caused much of that, as in the other areas of production, simply from a reduction of publishers and titles.

The introduction of actual digital inking added but a new component to the equation of creating comics. It consists of using a "wand" tool on a tablet or the screen to simulate the inking gestures without ink. But this skill has been extremely limited in usage, because of the cost and the difficulty of getting that natural look and versatility of line except over the most simplest of drawings. I only know of Alex Maleev and Brian Bolland who use it on their own art in the mainstream.

The misnomer "digital inking," the process of darkening and cleaning scanned pencil art lines in Photoshop, is not inking at all. [The term is] actually insulting to the traditional inkers. It's a cost-cutting measure and another exclusively comic book industry product, one that some pencil artists have requested in the goal of achieving more art sincerity.

But I feel what they've lost is the distinctive power of the ink through the missing weights, depth, textures, and other enhancing traits. Comic art commission clients know this, as do some editors. So I don't believe that the craft of inking will "die." But our present status could surely use a boost.

SSTOL: From a historical perspective, why is inking as a specialty such an important part of comic art?

Bob Almond: Deadlines. Inking was used on comic strips, and a form of it was created in the production of animation cells. But it was the comic book publishers who realized early on, when the medium was still young, that they could get more work out of their most popular and skilled artists by having their work inked by other artists. This way, a prolific superstar like Jack Kirby, for example, could draw and create most of the Silver Age Marvel Universe on his own. So it's a quantity tool.

Inking in general was also an essential part of the process, because the art wouldn't print properly, if at all, just in pencil. Successive decades later, technology allowed for such a possibility, but uninked art was used sparingly until recently. But as I discussed, it's also a quality tool, as the missing ink is very much missed.

In next Friday's second half of our interview, Bob Almond introduces us to the array of creators behind the Inkwell Awards, and also to some of the inkers who helped shape his own personal perspective on this unique artistic craft.

So, join us here in seven, won't you?

And that's your Comic Art Friday.

If you drop by this august establishment frequently, you'll recognize the name of comic book artist Bob Almond, whose titanic talent has graced many a Comic Art Friday. One of the most gifted inking specialists in the industry, Bob is a master at transforming pencil drawings into beautifully finished art.

Over the past few years, Bob has accepted about 30 commissions from me. It's fair to say that my art galleries would be drastically different were it not for the brush strokes and pen lines of the man other collectors and I affectionately call "The King of Ink."

Recently, Bob teamed with a stellar assemblage of comic industry insiders to create the Inkwell Awards, a soon-to-be-annual celebration of inking artists and their craft. Through his "Inkblots" column in Sketch Magazine, Bob developed the concept of acknowledging the often overlooked (and in my opinion, tragically undervalued) artists who, as Bob defines it, specialize in:

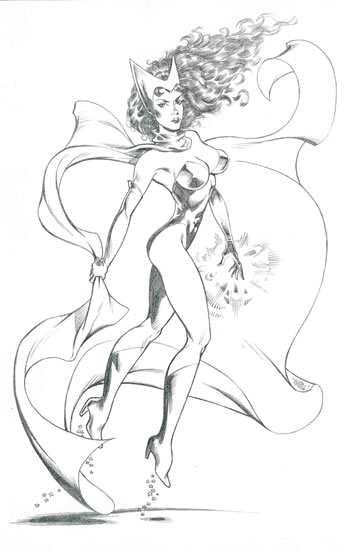

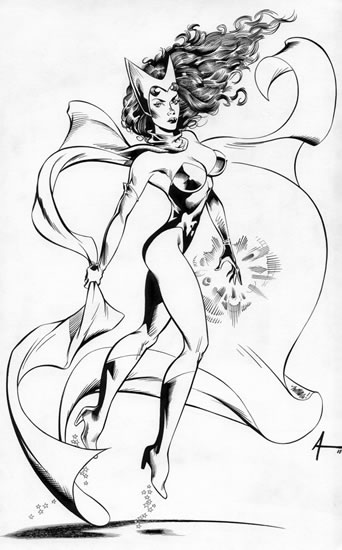

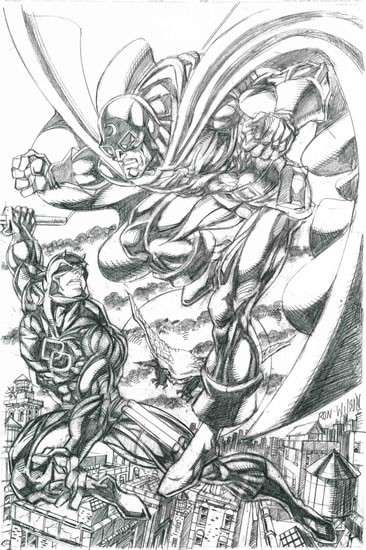

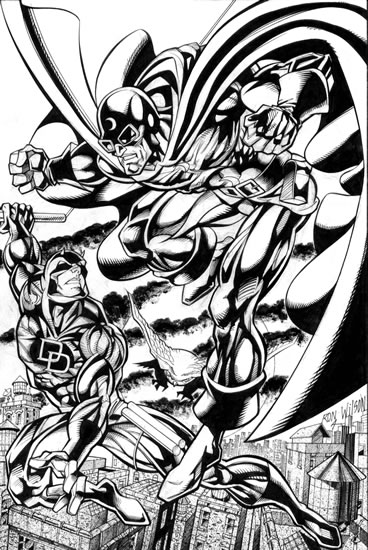

"the craft of enhancing an illustration through the means of redrawing pencil lines with ink and its related tools... in areas of — but not limited to — weight, space, depth, definition, contrast, texture, composition and design."Online balloting for the inaugural Inkwell Awards begins on April 1. In anticipation of the launch, Bob graciously consented to an interview with SSTOL. You're about to read the first half of this interview; we'll publish Part Two next Friday. To illustrate (no pun intended) the importance of "ink editing," I've chosen some of Bob's finest "before and after" projects from my collection to accompany this conversation.

SSTOL: Bob, what inspired you to create the Inkwell Awards? And why do you think that inkers don't get more recognition in the comics community?

Bob Almond: Actually, to combine these related questions into one answer, the fact that ink artists don't [get their just recognition] is what inspired me to create the awards. One reason for the latter is the fact that "inker" is almost exclusively a comic book industry product. As such, the name doesn't have a precedent for people comprehending what exactly s/he does.

In general, everyone knows what a penciler does, and they can easily determine that they draw. Same with the letterer, colorist, and even the editor. Not the inker. The common understanding from the public is that we fill in the blacks, or that we color, and, of course, that we "trace," which is the simplest and most ignorant of definition of our craft. If that was all we did, then anyone off the street could do it.

The other reason is that, for whatever reason, the status of inkers [within the comics industry] has been diminished of late. Their credits have been absent from some solicitations, reprint collection covers, and reprint sample art. Some major conventions haven't listed inkers in their guest lists, and some industry awards don't give them their own category. Inkers used to be one of the top three creator categories, but they've lost some leverage in that arena due to — in our opinion — less recognition for their work and lack of information.

We inkers certainly don't follow this line of work for the money. We do it for the love of the medium and craft, and for the credit. This is what motivated me to initiate an effort to give back to the invisible inker — often unsung, like the bassist of a band, who's not a rock star like the lead singer or guitarist.

We want to show appreciation to the ink artists, as well as have our site consisting of information and resources to help educate and inform the fans on what we do. Not to elevate our work to that of brain surgery or anything pretentious — we just feel it is an essential part of sequential art production in the area of quality control and storytelling enhancement.

SSTOL: In this age of computer graphics, is inking a dying art?

Bob Almond: Dying, no. Diminished, yes. But not necessarily due to computer tech. The comic book implosion of the '90s caused much of that, as in the other areas of production, simply from a reduction of publishers and titles.

The introduction of actual digital inking added but a new component to the equation of creating comics. It consists of using a "wand" tool on a tablet or the screen to simulate the inking gestures without ink. But this skill has been extremely limited in usage, because of the cost and the difficulty of getting that natural look and versatility of line except over the most simplest of drawings. I only know of Alex Maleev and Brian Bolland who use it on their own art in the mainstream.

The misnomer "digital inking," the process of darkening and cleaning scanned pencil art lines in Photoshop, is not inking at all. [The term is] actually insulting to the traditional inkers. It's a cost-cutting measure and another exclusively comic book industry product, one that some pencil artists have requested in the goal of achieving more art sincerity.

But I feel what they've lost is the distinctive power of the ink through the missing weights, depth, textures, and other enhancing traits. Comic art commission clients know this, as do some editors. So I don't believe that the craft of inking will "die." But our present status could surely use a boost.

SSTOL: From a historical perspective, why is inking as a specialty such an important part of comic art?

Bob Almond: Deadlines. Inking was used on comic strips, and a form of it was created in the production of animation cells. But it was the comic book publishers who realized early on, when the medium was still young, that they could get more work out of their most popular and skilled artists by having their work inked by other artists. This way, a prolific superstar like Jack Kirby, for example, could draw and create most of the Silver Age Marvel Universe on his own. So it's a quantity tool.

Inking in general was also an essential part of the process, because the art wouldn't print properly, if at all, just in pencil. Successive decades later, technology allowed for such a possibility, but uninked art was used sparingly until recently. But as I discussed, it's also a quality tool, as the missing ink is very much missed.

In next Friday's second half of our interview, Bob Almond introduces us to the array of creators behind the Inkwell Awards, and also to some of the inkers who helped shape his own personal perspective on this unique artistic craft.

So, join us here in seven, won't you?

And that's your Comic Art Friday.

Labels: Comic Art Friday, Hero of the Day

0 insisted on sticking two cents in:

Post a Comment

<< Home